5.1 TRANSPORTATION ELEMENT

The Transportation – Land Use Connection

The “Transportation – Land Use Connection” is an important

concept in land use and transportation planning. On the one hand, land uses

affect transportation by physically arranging the activities that people want

to access. Changes in the location, type, and density of land use change

people’s travel choices, thereby changing transportation patterns. On the other

hand, transportation affects land uses by providing a means of moving goods,

people, and information from one place to another.

Transportation systems play a very important role in

affecting urban structure. The debate over the “chicken and the egg” issue of

whether transportation influences land use development or whether land use

dictates transportation continues. The effect of past transportation decisions

and investments are evident in today’s development patterns with less than 10%

of the total population working in the central business districts of

traditional cities (Lowery, 1988). Thus, the transportation – land use

connection is one that cannot be ignored.

There are two important concepts that are central to

understanding the land use – transportation connection - accessibility and

mobility. Accessibility refers to the

number of opportunities, also called activity sites, available within a certain

distance of travel time. Due to the low-density development patterns that we

see today in most communities, the distances between activity sites such as

home, school, grocery store, etc., is increasing. As a result, accessibility

has become increasingly dependent on mobility, particularly on privately owned

vehicles. On the one hand, mobility can be seen as the consequence of spatial

segregation of different types of land uses, while on the other hand, it can

also be seen as contributing to increased separation of land uses. Improvements

in the transportation field have enabled people to travel longer distances in

the same amount of time, which has resulted in the growing segregation between

activity sites, especially between home and work. In today’s urban scenario,

the value of land is heavily dependent on the transportation network providing

access to it. Or in other words, the location of a place within the

transportation network determines its value and use.

Land development is influenced by a large number of forces

shown in the figure below. Infrastructure, which is comprised of sewer, water,

utilities and transportation play an important role in influencing land use

patterns. Transportation in turn is affected by individuals, private sector,

federal government, state and local governments. As mentioned earlier, the most

significant role that transportation plays in land development is affecting

access to land. Transportation systems have the potential to indirectly affect

land development by either inducing new development or altering the pattern of

development. Even through a transportation improvement may not bring growth to

a region in terms of number of households or square feet of developed area, it

may affect the location pattern of land uses. However, due to the large number

of factors affecting land use patterns, transportation may be considered just a

part of a complicated process of land development.

Transportation’s Role in Land Use

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sewer

Water

Utilities

Transportation

|

|

|

|

|

Should Urban Sprawl be a Concern?

Most metropolitan communities that

have become the victims of urban sprawl are paying a heaving price through the

increase in congestion, long commutes, loss of natural resource land, vanishing

open spaces, air and water pollution, neighborhood and inner city

deterioration, and the rising cost of public services. In 1950, 70% percent of

the population in metropolitan areas lived in central cities. By 1990, that

situation had reversed, with more than 60% percent living in suburbs (Rusk

1993). Over the past few decades, developed land area and vehicle use increased

at a pace faster than population growth (Federal Highway Administration 1993).

The Transit Cooperative Research

Program (TCRP) sponsored by the Federal Transit Administration published a

report on the “Costs of Sprawl – Revisited” (report 39) in 1988. The following

are a few key points from this report on the positive and negative impacts of

sprawl:

Negative Impacts of Sprawl:

·

Higher infrastructure and public operating

costs: This includes the cost of local and regional roads, water, sewer, school

systems, etc. and was found to be higher in low-density developments than in

compact developments with centralized services.

·

Higher aggregate land costs: The total land

costs associated with sprawl driven development is higher as more land is

consumed then under compact development patterns.

·

Consumes prime agricultural land: Sprawl

consumes prime agricultural land from farming use than more compact forms of

development. This also lowers the productivity of the farmland near sprawl

developments due to the difficulty of conducting efficient farming operations.

·

Lack of community sense: Sprawl driven

developments do not lend themselves easily to the formation of cohesive

communities. The households lack a sense of belonging to the community in such

environments.

·

Worsens pollution: Sprawl worsens the overall

air pollution in a metropolitan area due to the increased number of vehicle

miles traveled. It also lowers water quality by increasing the amount of

impervious surface, thereby increasing runoff and erosion.

·

Encourages deterioration of the inner city:

Sprawl encourages businesses and households to leave the inner city allowing

them to move to the suburbs in search of cheaper land. As a result, the

economic base of the inner city is weakened.

Positive Impacts of Sprawl:

·

Lower housing costs: Sprawl has lower housing

costs because it does not limit the amount of development and land is also

cheaper in the suburban fringes than within the city limits.

·

Supports the American dream of low-density

living: Sprawl encourages the growth of low-density residential neighborhoods,

which are preferred by a large percentage of the population.

·

Enhances personal and public open space: Sprawl

provides more open space directly accessible to the individual households in

the form of larger private yards than may be possible in more compact forms of

development. It promotes the American dream of a big yard and a house set back

from the street.

·

Lower crime rate: Low-density development

patterns have lower crime rates.[i]

How Does Transportation Impact Us?

Transportation touches the lives of

nearly everyone every day. Whether traveling to work, school, or to a favorite

vacation spot, Wisconsin's transportation network will provide the means to get

here. Working for Wisconsin's future

Wisconsin's transportation infrastructure has come a long way in a single

generation. It has developed from a system of two-lane roads and highways,

grass landing strips, wooden piers, and locomotives, to a network of multi-lane

divided highways, airports, modern water ports, efficient transit systems and

rail lines linking the state with markets throughout the world.

For the traveling public, Wisconsin

had 3,733,077 licensed motorists

at the end of 1999 and more than 4.7

million registered vehicles can travel on over 111,500 miles of highways,

roads, and streets. This includes 12,000 miles of state and interstate highways,

and 98,000 miles of locally-owned county, town and municipal routes with 13,300 bridges spanning over

these roadways.

Within the state's communities, 68 public bus and shared-ride taxi systems

connect people with economic opportunities while reducing traffic congestion.

The State Airport System Plan includes 131 public access airports, 9 offering scheduled flights

that carry over 4 million passengers annually. Amtrak transports more than

425,000 people to Chicago, Minneapolis and other points across the country

every year.

For business and industry,

Wisconsin provides efficient and cost-effective transportation alternatives to

get products to market. In addition to its safe and efficient network of

highways for trucks, Wisconsin has 4,500

miles of track and 12 railroads handling 94 million tons of cargo

along with 15 major ports.

And if it has to be there fast, Wisconsin's airports handle 120,000 tons of

cargo annually.

Currently, nearly 12% of all Wisconsin work trips are made by

walking and bicycling. In several cities, almost 20% of trips are

made by these modes. WisDOT has recently partnered with the Bicycle Federation

of Wisconsin to provide the state bicycle map. The Rustic Roads System,

created in 1973, provides bikers, hikers, and motorists an opportunity for

leisurely travel through some of Wisconsin's scenic countryside. To date, 86 rustic roads have been

preserved for purposes of recreational enjoyment covering 461 miles in 49

Wisconsin counties.

Wisconsin Traffic Crash

Facts

1999 Facts and Figures

1999 Facts and Figures

·

744

persons were killed in Wisconsin motor vehicle traffic crashes. (36% involved

Alcohol, 27% involved Speed, and 14% involved both Speed and Alcohol).

·

61,577

persons were injured in 41,345 reported injury crashes and 674 fatal crashes.

·

An

average of 2.0 persons were killed every day on Wisconsin highways.

·

The

fatality rate per 100 million miles of travel was 1.31 in 1999, compared to

1.26 in 1998.

·

Of

the 439 drivers who were killed and tested for alcohol concentration, 159

drivers (36%) had an alcohol concentration of .10 or above and were legally

intoxicated.

·

55

pedestrians were killed, compared to 64 in 1998.

·

Of

the 55 pedestrians killed, 9 (16%) had an alcohol concentration of .10 or

above.

·

18

bicyclists were killed, compared to 11 in 1998.

·

65

motorcyclists were killed, the same number as in 1998.

·

39%

of persons killed in passenger cars (for whom belt use was reported) were using

safety restraints.

·

73%

of all motorcyclists killed in crashes (for whom helmet use was reported) were

not wearing helmets.

·

60%

of all crashes occurred on county trunk highways and local roads.

·

The

total number of registered vehicles was 4,713,643 compared to 4,449,217 in 1998

(a 5.9% increase).

·

The

total number of licensed drivers was 3,733,077 compared to 3,709,957 in 1998 (a

0.6% increase).

A good transportation system is fundamental

to the physical and economic functioning of any community. Spatially, a transportation system is evaluated

on how well people, goods, and services are distributed from one place to

another. In economic terms, a

transportation system can be viewed as to how much traffic volume and access is

available to support local business activity.

Since a majority of residents in the Town of Rushford commute outside

the town for employment opportunities, the current transportation network is

important to town officials and residents. On December 31 of 1998 the WIDOT

reported a total 107,321 licensed drivers in Winnebago County.

A good transportation system is fundamental

to the physical and economic functioning of any community. Spatially, a transportation system is evaluated

on how well people, goods, and services are distributed from one place to

another. In economic terms, a

transportation system can be viewed as to how much traffic volume and access is

available to support local business activity.

Since a majority of residents in the Town of Rushford commute outside

the town for employment opportunities, the current transportation network is

important to town officials and residents. On December 31 of 1998 the WIDOT

reported a total 107,321 licensed drivers in Winnebago County.

The transportation network in the

Town of Rushford consists of a combination of state, county, and town roads

containing almost 70 miles of roadway.

The distribution of state, county, and local road mileage in the Town of

Rushford can be seen in the accompanying graphic. Town roads dominate the amount of road miles

in Rushford by a significant margin. A

total of 44.73 miles of town roads exist in the Town of Rushford, while 14.23

miles are county highways, and 9.60 miles are state highways. Recognizing the amount of roadway miles

attributed to local roads is especially important because public services such

as general road maintenance and snow removal can present fiscal concerns for

communities such as Rushford.

STATE HIGHWAYS

The primary regional highway

serving the greater Rushford area is Highway 21, which passes through the

northern portion of the town extending west to Redgranite and east to

Oshkosh. A secondary regional highway

also serves the Town of Rushford, which is Highway 116/91. Highway 116/91 passes through the

southeastern tip of Rushford and extends west to Berlin and east to Oshkosh. These two highways are the primary

thoroughfares serving the City of Oshkosh from western and central

Wisconsin. Neither of these highways are

under construction within the Town of Rushford, nor have they been recently

worked on. The Wisconsin Department of

Transportation (WISDOT) does not have any proposals for future construction of

Highways 21 or 116. A review of Wisconsin Department of Transportation 2000

Class II Roadway's determined that the Town of Rushford currently contains none

of these classified roadway's. Proximity to urbanized areas such as Oshkosh,

Appleton, Berlin, and Omro have been viewed as a strength of the current transportation

network which includes state, county, and local roads.

COUNTY HIGHWAYS

The county highways serving the

Town of Rushford are Highways K and E.

Highway K begins at the intersection of Highway 21 near the northern

part of Rushford, passes through the unincorporated Village of Eureka, and

extends east into the City of Oshkosh.

Highway E, on the other hand, enters the Town of Rushford from the

south, passes through Eureka, and extends east into the City of Oshkosh. These two highways intersect in Eureka,

making them the primary roads serving the Town of Rushford. Currently, there is no construction

occurring on either of these roads, nor are there any future proposals for

construction.

LOCAL ROADS

Local roads in the Town of Rushford

consist of an interweaving grid pattern serving residences, town facilities,

county parks, public landings, county highways, state highways, etc. Local roads primarily serve as

"Collectors"

that connect residences, public facilities, parks, county or state highways,

town centers, or major activity centers.

As local roads make up the abundance of road mileage in Rushford, it

becomes very important to consider maintenance, capacity, volume, and access of

these roads, as they pertain to costs and other fiscal capabilities of the Town

of Rushford.

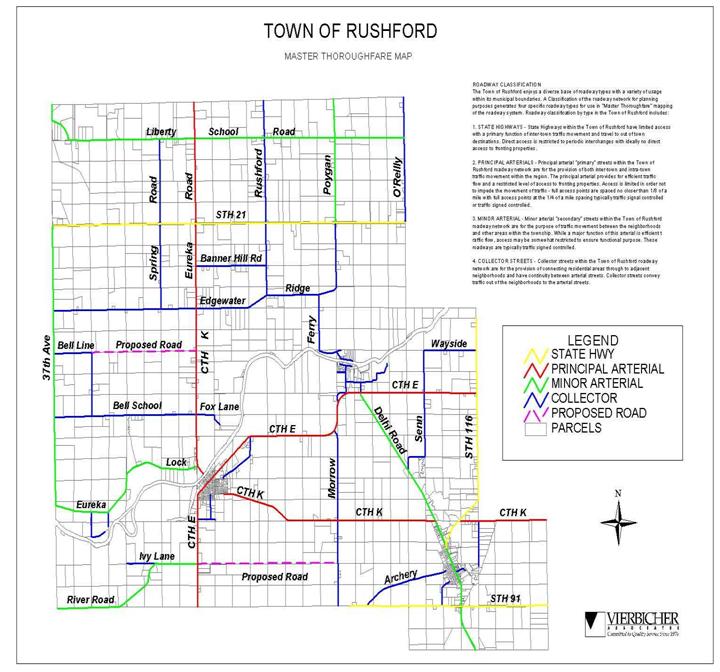

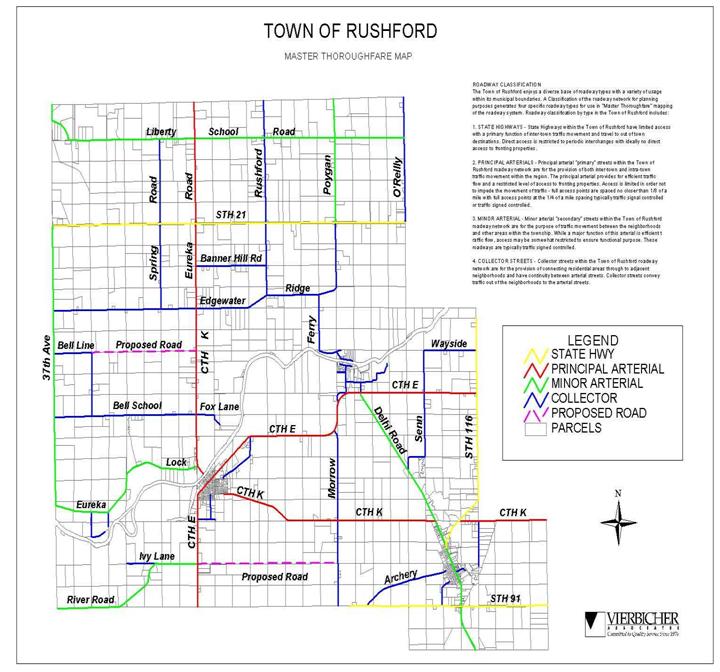

ROADWAY

CLASSIFICATION

ROADWAY

CLASSIFICATION

The Town of Rushford enjoys a

diverse base of roadway types with a verity of usage within its municipal

boundaries. A Classification of the roadway network for planning purposes

generates four specific roadway types for use in "Master

Thoroughfare" mapping of the roadway system. Roadway classification by

type in the Town of Rushford includes:

1.

STATE HIGHWAYS - State Highways within the Town

of Rushford have limited access with a primary function of inter-town traffic

movement and travel to out of town destinations. Direct access is restricted to

periodic interchanges with ideally no direct access to fronting properties.

2.

PRINCIPAL ARTERIALS - Principal arterial

"primary" streets within the Town of Rushford roadway network are for

the provision of both inter-town and intra-town traffic movement within the

region. The principal arterial provides for efficient traffic flow and a

restricted level of access to fronting properties. Access is limited in order not

to impede the movement of traffic - full access points are spaced no closer

than 1/8 of a mile with full access points at the 1/4 of a mile spacing

typically traffic signal controlled or traffic signed controlled.

3.

MINOR ARTERIAL - Minor arterial "secondary"

streets within the Town of Rushford roadway network are for the purpose of

traffic movement between the neighborhoods and other areas within the township.

While a major function of this arterial is efficient traffic flow, access may

be somewhat restricted to ensure functional purpose. These roadways are

typically traffic signed controlled.

4.

COLLECTOR STREETS - Collector streets within

the Town of Rushford roadway network are for the provision of connecting

residential areas through to adjacent neighborhoods and have continuity between

arterial streets. Collector streets convey traffic out of the neighborhoods to

the arterial streets.

COLLECTOR STREETS - Collector streets within

the Town of Rushford roadway network are for the provision of connecting

residential areas through to adjacent neighborhoods and have continuity between

arterial streets. Collector streets convey traffic out of the neighborhoods to

the arterial streets.

The "Thoroughfare System"

provides the framework of streets and access upon which the Comprehensive Plan

is based. There is a direct relationship between the location of specific sites

within this system and the intensity of land use, which is appropriate for that

area. The Town of Rushford's Master Thoroughfare Plan/Map provides for the safe

and efficient movement of people and goods throughout the community and the

region.

With respect to sound traffic

planning, rule of thumb principals for traffic demand can be evaluated by

considering the following capacity values for passenger cars on a given

roadway:

|

Road Size

|

Average Daily Traffic Capacity

|

|

|

8,000 – 12,000 ADT

|

|

4 Lane

|

16,000 – 24,000 ADT

|

|

6 Lane

|

24,000 – 36,000 ADT

|

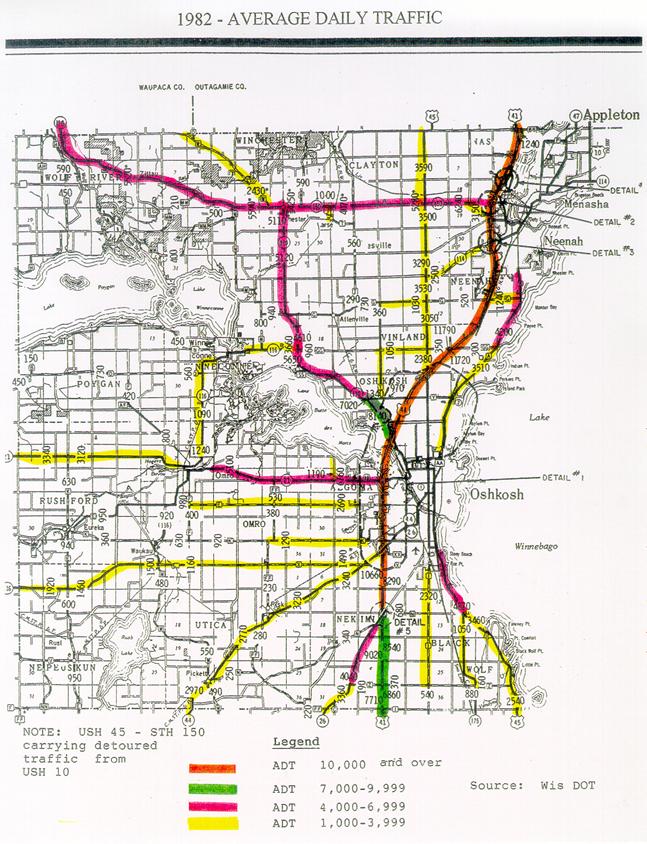

ROADWAY USAGE

The Wisconsin Department of Transportation has assumed the role of obtaining

traffic counts along various federal, State, county, and local roads throughout

Wisconsin.

The department usually obtains these

counts every three years, the last being in 1997. Recognizing the amount of traffic that nearby

roads and highways endure on a daily basis is a good indicator regarding

longevity and capacity. Also, traffic

counts are a sign of how timely it is for residents commuting to nearby

employment centers. An analysis of

travel times from the U.S. Census, concluded that most residents travel between

20-29 minutes to their place of work.

Being that Oshkosh is the major employment center in the region, and is

less than 20 miles away from Rushford, there is reason to believe that traffic

volumes are a concern to Rushford residents.

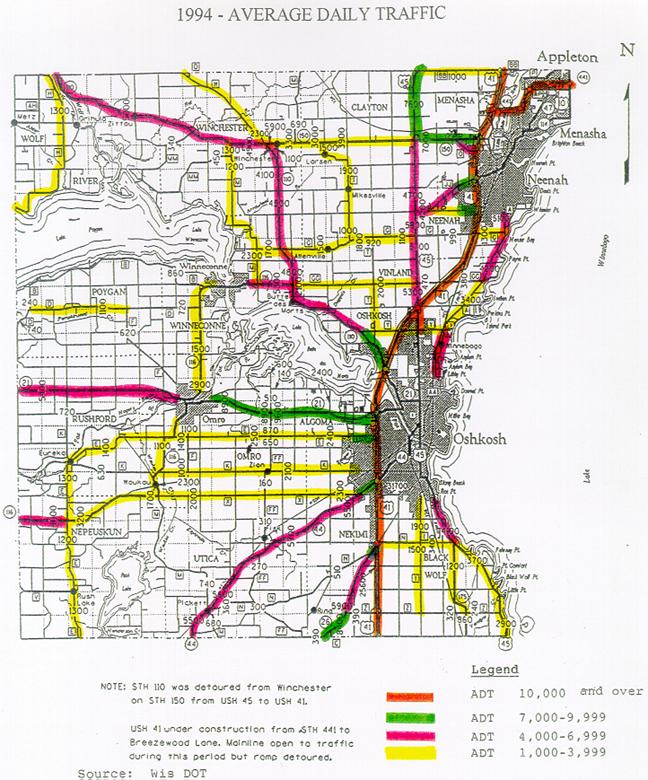

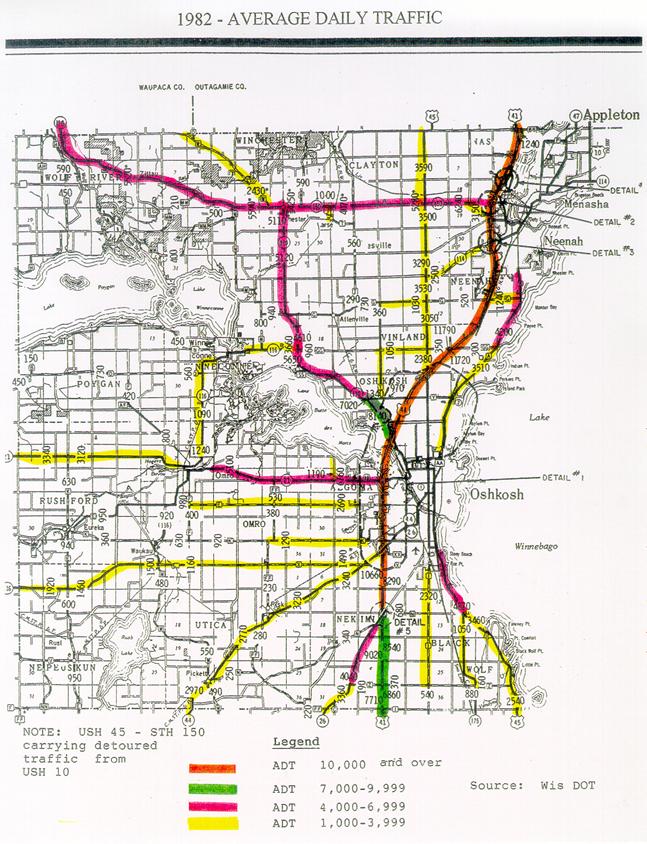

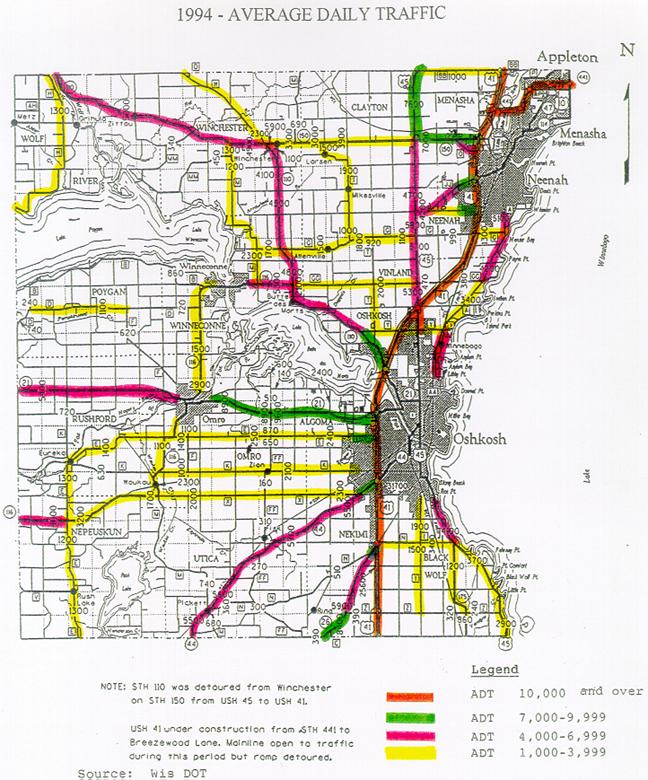

At the County level significant

increases in rural roadway usage have taken place between 1982 and 1994. There

has clearly been a correlating impact to the usage of the roadway system with

respect to the increase in rural residents in the outlying areas of Winnebago

County. These impacts include the need for additional attention by local units

of government in the areas of safety, maintenance and upkeep costs related to

their roadway networks.

Understanding that traffic volumes have increased significantly on Rushford’s

major arterial and connector roads raises future concern with respect to the

safety, capacity and longevity of the towns roadway system. It is clear from

1991 – 1997 average daily traffic counts that STH 21, CTH K, CTH E, STH 116,

and STH 91 are serving as commuter travel routs of choice. As development

continues to occur the town should undertake measurers to limit new access onto

these major travel corridors in order to ensure safety.

Table 2 shows various traffic

counts taken at select places in the Town of Rushford for the years 1991, 1994,

and 1997. The largest increase observed

was east of Eureka on Highway K, which experienced a 41% increase in average

number of vehicles per day.

Other significant

increases occurred south of Highway 21 on County Trunk K (30.4%), and west of

County Trunk E on Highway 116 (29.4%).

These traffic increases could certainly pose a threat to current traffic

patterns and infrastructure conditions in the Town of Rushford. Figure 20 presents the percentage change in

traffic counts at select locations from 1991 to 1997, in graphical form. Past and current trends are apparent.

Other significant

increases occurred south of Highway 21 on County Trunk K (30.4%), and west of

County Trunk E on Highway 116 (29.4%).

These traffic increases could certainly pose a threat to current traffic

patterns and infrastructure conditions in the Town of Rushford. Figure 20 presents the percentage change in

traffic counts at select locations from 1991 to 1997, in graphical form. Past and current trends are apparent.

Given the moderate growth in the

county over recent years, and the growth that Oshkosh has experienced due to

retail business and manufacturing employment opportunities, one can only assume

that this trend will persist in future years.

As a result, additional pressures on existing roads in the Town of

Rushford will likely occur in the future, presenting increased maintenance and

construction costs.

As this growth occurs town

officials will want to be cognoscente of the creation and placement of new

arterial roadways and collector roadways within the community. Maintaining

fluid traffic movement through the community to avoid traffic problems such as

congestion, safety, speed, noise and others is the objective of sound

transportation policy. As a rule of thumb, arterial spacing should follow the

following guidance:

|

Arterial Spacing Principals

|

|

|

Net Residential Units Per Acre Being

Served

|

Location

|

Spacing Distance

|

|

|

Downtowns

|

1/8 mile or less

|

|

6-10 units per acre

|

High Density

|

¼ to ½ mile

|

|

4-6 units per acre

|

Medium Density

|

½ to 1 mile

|

|

2-4 units per acre

|

Low Density

|

2 miles

|

|

|

Semi - rural

|

3 miles

|

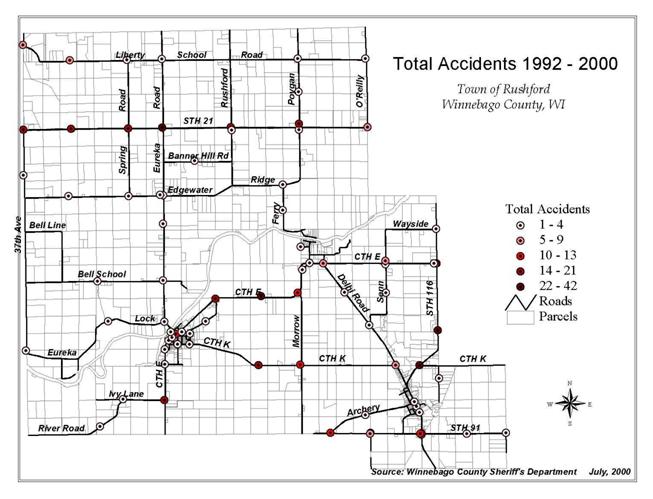

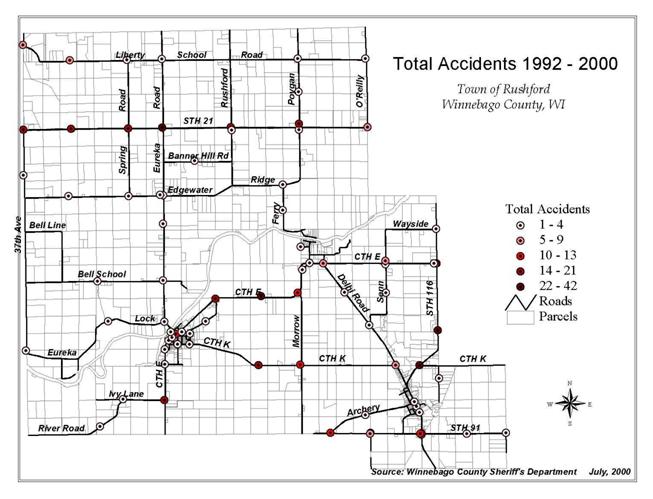

ROADWAY SAFETY

With mounting pressure on the

existing roadway system due to growth and development the Town of Rushford has

experienced its share of safety issues.

Accidents at many Rushford

intersections have reached levels of concern that are cause for the careful

planning of future loading that could occur through new developments. When intersectional

accident statistics are overlaid on top of the roadway map it can be noted that

a majority of recorded accidents since 1992 have occurred at intersections

involving the State and County highway system within the township.

|

Accident Type

|

1992 Reports

|

1993 Reports

|

!994 Reports

|

1995 Reports

|

1996 Reports

|

1997 Reports

|

1998 Reports

|

1999 Reports

|

2000 Reports

|

Average Through 1999

|

Total Average

|

|

ACCIDENT FATAL

|

1

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0.38

|

0.44

|

|

ACCIDENT HIT & RUN

|

0

|

2

|

2

|

2

|

0

|

3

|

0

|

2

|

0

|

1.38

|

1.22

|

|

ACCIDENT INFORMATION

|

0

|

2

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0.25

|

0.22

|

|

ACCIDENT INJURY

|

17

|

6

|

13

|

12

|

14

|

12

|

14

|

12

|

3

|

12.50

|

11.44

|

|

ACCIDENT PROPERTY DAMAGE

|

34

|

44

|

59

|

61

|

70

|

49

|

47

|

53

|

23

|

52.13

|

48.89

|

|

ACCIDENT UNKNOWN

|

0

|

2

|

1

|

2

|

0

|

1

|

2

|

0

|

0

|

1.00

|

0.89

|

As safety issues grow as a concern

within the township, consideration of speed control measurers and traffic

controlling signage and lighting must also be undertaken. According to the

Wisconsin Department of Workforce Development, December 2000, Winnebago County,

“Workforce Profile”[ii]:

“Winnebago County workers are very

mobile. Of the 94,200 residents of the county who have jobs, 40.2% (37,883)

work outside the county. The largest number commute to jobs in Outagamie

County, and that is mostly within the Fox Cities area. Winnebago County

actually gains 2,471 workers in the exchange with Outagamie County. A large

part of this inter-county commute around the Fox Cities relates to jobs in the

paper industry.

Commuters get around Winnebago

County via Highway 41, the main corridor running through the hart of the Fox

Valley. The 441 express way makes the commute for over 2,500 from Calumet

County to Winnebago County much easier than at any time before completion of

that route. It also affords faster access from the Green Bay area.

WINNEBAGO COUNTY COMMUTING PATTERNS

|

|

Commute Into

|

Commute From

|

Net Commute

|

Outagamie County

|

8,942

|

11,413

|

2,471

|

|

Fond du Lac County

|

1,316

|

1,925

|

609

|

|

Waupaca County

|

351

|

931

|

580

|

|

Calumet County

|

375

|

2,622

|

2,247

|

|

Elsewhere

|

2,168

|

3,604

|

1,436

|

|

Total

|

13,092

|

21,238

|

8,146

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Work in Winnebago County

|

56,317

|

|

|

Commuters to Winnebago County come

from a 16 county area. They travel from Oconto County in the north, Portage

County to the west, Columbia County to the southwest, Door County from the

northeast, Sheboygan, Manitowoc, and Calumet Counties to the east and Fond du

Lac County to the south of the area. Outbound commuters travel to seven other

counties, but most traffic is to Outagamie and Fond du Lac counties. While most

commuters are manufacturing workers, in recent years we have seen an increase

in professional and technical workers expanding their commuting areas from

work. From the Fox Cities to Oshkosh is one of the state’s hottest job growth

areas.” As these commuter patterns continue to expand, further evidence of the

to maintain the safety of Rusford’s roadway system is established.

As a working Philosophy the Town of

Rushford will seek “the least control that provides good operations and a

satisfactory level of safety” when implementing traffic control policies and

stratigies.

Access management

The purpose of access management at the Wisconsin Department

of Transportation is to maintain the operational efficiency and safety of state

highways by controlling the type, number, and location of access points to the

highway system.

Wisconsin's state highway system comprises 12,000 miles of

state and Interstate highways.

·

Access points to the state highway system

automatically increase the potential for crashes by introducing cross traffic

on a free-flowing highway.

·

Access points create operational problems by

slowing the overall traffic flow to allow for slower vehicles that are pulling

off the highway or onto the highway. High volumes of vehicles such as large

trucks or farm machinery can further add to these operational problems.

·

Cost impacts of access are placed on the

individual/organization requesting the access.

In the 2000 State Highway Plan, WisDOT concludes that

current funding levels will not alleviate all the highway system's congestion

problems. With higher capacities and increased congestion, one of the major

tools that will allow our existing highway system to perform with acceptable

efficiency and safety is access management.

WisDOT uses the following tools to manage the highway

system:

·

Driveway permits

·

Trans 233

·

Controlled access projects

Managing access is key to highway safety. More access points

on a roadway means an increased number of crashes.

|

Access points per mile

|

Crash rate per million vehicle miles traveled

|

|

.2

2.0

20.0

|

1.3

2.7

17.2

|

Access management - driveway permits

Driveway permits:

·

Any private access to the state highway system

requires a permit.

·

The permit grants the right to work on state

highway right of way, and the right to access the highway under certain

conditions or restrictions.

·

Driveway permits are not permanent rights and

may be revoked by WisDOT if misuse occurs. Permits may also be revoked if a

highway improvement project requires the elimination of access points to maintain

or increase the free flow of traffic for capacity and safety reasons.

·

Issuing or denying a driveway permit is based on

specific standards such as highway geometry, sight distance, and proximity to

other access points.

The type and maximum size of access is determined by the

intended use of the property. A single-family dwelling may only require a

simple driveway while a commercial property may require more extensive access.

Costs of constructing and maintaining private access points

are borne by the property owner and not by WisDOT.

Determining the type of access required is based on standard

land-use trip generation guidelines.

Access management - Trans 233

Any division or assemblage of lands abutting existing state

highways is subject to review by WisDOT. This includes subdivision plats,

county plats, condominium plats, certified survey maps, plats of survey or a

plain legal description with no survey.

The review ensures:

·

Any access and internal-street system to the

land division serves the maximum amount of landowners, which in turn will limit

future access requests to the state highway.

·

Drainage impacts to state highways are minimized

or controlled.

·

Proper setbacks are used to minimize future

disruptions to the landowner or costs to the public if a highway expansion is

needed.

For more information on Trans 233 visit http://www.dot.state.wi.us/dtid/bhd/trans233.html.

Access management - Controlled access projects

Entire segments of highways can be access controlled through

the completion of controlled access projects. These projects require a public

hearing process to inform all impacted parties and to solicit their input. This

type of project allows WisDOT to then readily manage public and private access

in the future along those segments.

By applying uniform standards such as these, property owners

can be ensured of a fair and equal review.

Effective access management makes our highways safer,

reduces the need for major road expansion by extending the usefulness of

existing highways, and produces a more consistent travel flow. This helps limit

congestion, reduces fuel consumption and improves air quality.

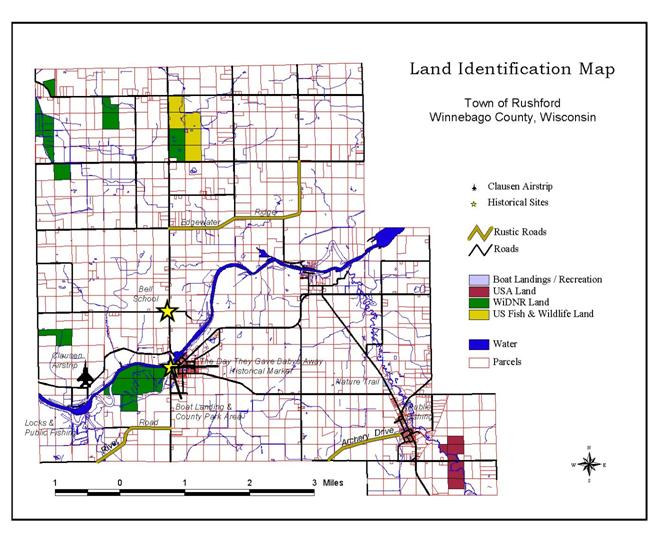

Wisconsin's Rustic Roads

A Positive Step Backward

Creation

The Rustic Roads System in Wisconsin was created by the 1973

State Legislature in an effort to help citizens and local units of government

preserve what remains of Wisconsin's scenic, lightly traveled country roads for

the leisurely enjoyment of bikers, hikers and motorists.

Unique brown and yellow signs mark the routes of all

officially-designated Rustic Roads. These routes provide bikers, hikers, and

motorists with an opportunity to leisurely travel through some of Wisconsin's

scenic countryside.

A small placard beneath the Rustic Roads sign identifies

each Rustic Road by its numerical designation within the total statewide

system. Each Rustic Road is identified by a 1- to 3-digit number assigned by

the Rustic Roads Board. To avoid confusion with the State Trunk Highway

numbering, a letter "R" prefix is used such as R50 or R120. The

Department of Transportation pays the cost of furnishing and installing Rustic

Roads marking signs.

An officially designated Rustic Road shall continue to be

under local control. The county, city, village or town shall have the same

authority over the Rustic Road as it possesses over other highways under its

jurisdiction.

A Rustic Road is eligible for state aids just as any other

public highway.

Program Goals

·

To identify and preserve in a natural and

essentially undisturbed condition certain designated roads having unusual or

outstanding natural or cultural beauty, by virtue of native vegetation or other

natural or man-made features associated with the road.

·

To provide a linear park-like system for

vehicular, bicycle and pedestrian travel for quiet and leisurely enjoyment by

local residents and the general public alike.

·

To maintain and administer these roads to

provide safe public travel, yet preserve the rustic and scenic qualities

through use of appropriate maintenance and design standards, and encouragement

of zoning for land use compatibility, utility regulations and billboard control.

What is a Rustic Road?

To qualify for the Rustic Road program, a road:

·

Should have outstanding natural features along

its borders such as rugged terrain, native vegetation, native wildlife, or

include open areas with agricultural vistas which singly or in combination

uniquely set this road apart from other roads.

·

Should be a lightly traveled local access road,

one which serves the adjacent property owners and those wishing to travel by

auto, bicycle, or hiking for purposes of recreational enjoyment of its rustic

features.

·

Should be one not scheduled nor anticipated for

major improvements which would change its rustic characteristics.

·

Should have, preferably, a minimum length of 2

miles and, where feasible, should provide a completed closure or loop, or

connect to major highways at both ends of the route.

·

A Rustic Road may be dirt, gravel or paved road.

It may be one-way or two-way. It may also have bicycle or hiking paths adjacent

to or incorporated in the roadway area.

- The maximum speed limit on

a Rustic Road has been established by law at 45 mph. A speed limit as low

as 25 mph may be established by the local governing authority.

The Town of Rushford is currently

home to three state designated rustic roads. Eureka Lock Road, Archery and

Edgewater Ridge have each been designated by the program. By being designated

by the rustic roads program, these roads serve the town by protecting its rural

character by the restrictions that have been placed on them. As the town

continues to grow and develop, additional attention should be given to

designating new roadways as rustic roads as a means to preserve rural character

and to continue to provide a safe transportation system throughout the

township.

One of the primary functions of Town Boards is to maintain the

local roadway system. This includes construction, resurfacing and maintenance.

As the number of rural non-farming residents continues to increase throughout

Wisconsin, communities find themselves taking the opportunity to approach

roadway management from a new perspective. With existing residents wanting to

preserve and maintain rural character and new residents placing a greater

emphasis on “scenic quality” the notion of establishing a scenic rural roads

program is gaining favor.

Road management that takes into account the scenic/rural

character of roads in a way that is much like how a tourist would view a

roadway, placing emphasis on more than just road width, line-of-site, and

pavement conditions. To this end it may be beneficial for local officials to

identify “scenic rural roads” and develop “roadside construction/maintenance”

policies to guide roadwork on these roads, as well as other local roads. One

method to accomplish this and to consider which local roads might be

appropriate for submission and designation as rustic roads would be to conduct

the following exercise[iii]:

Scenic Rural Roadway Evaluation Scorecard

Evaluating

entire road Evaluating a segment of

the road

Location of road segment if appropriate ___________________________

Name of Evaluator

______________________________________________

*

Read the criteria statement

in each of the following boxes. Record the appropriate points in the box

provided for each of the criteria that apply to the road or road segment being

evaluated. When done with both the positive and negative evaluation scoring,

total the points given and write that figure in the total box provided. Half

points may be applied to the below features that are not equal to the “norm”

but deserve some recognition, as long as the total points possible per

attribute is not exceeded.

Positive Attributes:

Attribute

|

Point Value

|

Points

Given

|

|

Continuous or intermittent

large trees on one side of the road for less than 100 yards

|

1

|

|

|

Continuous or intermittent large

trees on both sides of the road for less than 100 yards

|

2

|

|

|

Continuous or intermittent

large trees on both sides of the road with canopy over the road for less than

100 yards

|

3

|

|

|

Continuous or intermittent

large trees on one side of the road for more than 100 yards

|

2

|

|

|

Continuous or intermittent

large trees on both sides of the road for more than 100 yards

|

4

|

|

|

Continuous or intermittent

large trees on both sides of the road with canopy over the road for more than

100 yards

|

6

|

|

|

Pond adjacent to the road

|

2

|

|

|

|

1

|

|

|

Bridge on the road

|

1

|

|

|

Stone, covered or historic

bridge on the road

|

3

|

|

|

Stone wall or wooden fence

|

1

|

|

|

Picturesque farmstead or

unusual building

|

2

|

|

|

Historic structure or

archeological site

|

2

|

|

|

Wildlife viewing are from

road (domestic buffalo, elk, etc., or natural deer, turkeys, etc.)

|

2

|

|

|

Agricultural pattern

(orchard, contour plowing, etc.)

|

1

|

|

Attribute

|

Point Value

|

Points

Given

|

|

|

1

|

|

|

Vista of hill on the road

|

2

|

|

|

Vista “variety” (trees,

fields, wetlands, hills, water, etc.) from road

|

2

|

|

|

Hill on road

|

1

|

|

|

Vista variety (trees,

fields, wetlands, hills, water, etc.) from top of hill on road

|

3

|

|

|

Enframed, enclosed or

valley view

|

2

|

|

|

Panoramic or distant view

|

2

|

|

|

Ephemeral effect (sunset,

mist, reflection)

|

2

|

|

|

Seasonal effect (ice

formations, brilliant foliage)

|

2

|

|

|

View of lake or river from

road

|

2

|

|

|

View of waterfall, cliff or

rock outcrop

|

2

|

|

|

View of wetland, bog, or

remnant prairie from road

|

2

|

|

|

Park like area (including

cemeteries) adjacent to road

|

1

|

|

|

Public park adjacent to

road

|

2

|

|

|

View of “specimen tree”

from road

|

1

|

|

|

Hill with limited roadway

visibility (traffic hazard – slow down)

|

2

|

|

|

Curve with limited

visibility (traffic hazard – slow down)

|

2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

TOTAL POINTS AWARDED

|

|

|

Negative attributes:

Attribute

|

Point Value

|

Points

Given

|

|

Sever/significant erosion

|

|

|

|

View of gravel pit or sand

mining operation

|

|

|

|

Utility line, corridor, or

substation

|

|

|

|

Strip development

|

|

|

|

Incompatible building

(style, material, lot size, non-farm, non-residential)

|

|

|

|

View of junk yard or

landfill

|

|

|

|

Storage tanks

|

|

|

|

Obtrusive signage (size,

too many, flashing)

|

|

|

|

View of unkept buildings

|

|

|

|

Monotony – “same old same

old” landscape

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

TOTAL POINTS AWARDED

|

|

|

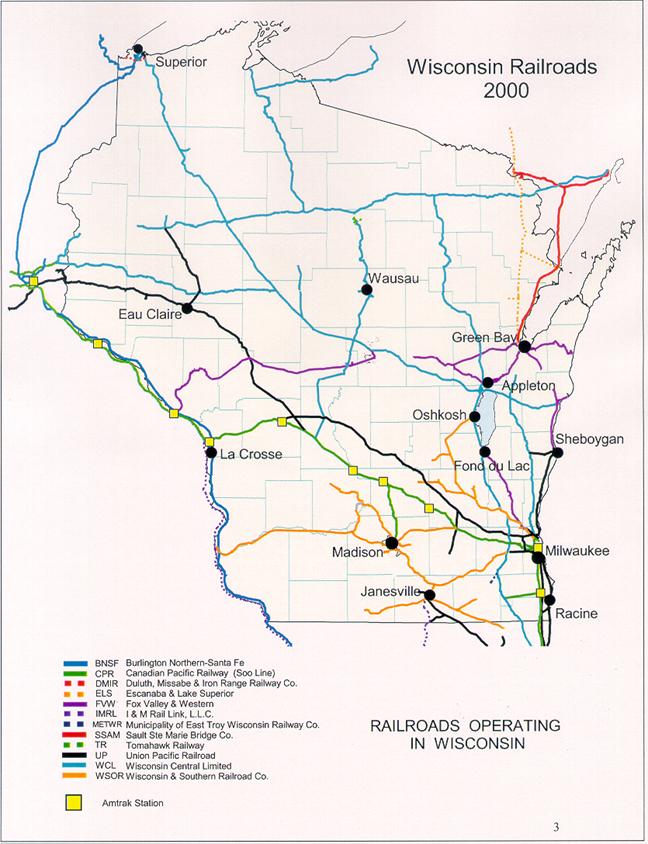

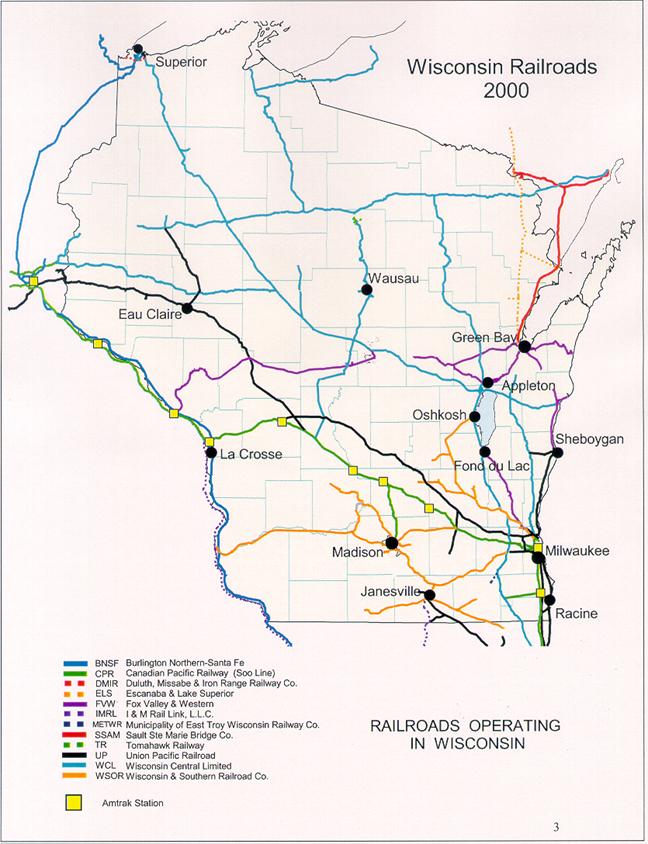

RAIL SERVICE

Rail service is available in the

City of Oshkosh via Wisconsin Central Ltd., and Wisconsin and Southern Railroad

Co. Both rail lines operate with

multiple trains on a daily basis to move products throughout the United States

and Canada. No commuter service is

available.

Significant changes are taking

place with railroads in Wisconsin. Both freight and passenger rail are

constantly evolving to meet changing needs. WisDOT needs to continue rail

planning to enhance the Wisconsin Rail

System and to meet the future transportation needs of the state. With an

increasing population and a steady growth in highway traffic congestion,

freight and passenger rail will become even more vital to the state’s

transportation system.

Freight Rail

Railroads have been part of

Wisconsin since 1847, twenty years after the origin of rail in the United

States. Two factors greatly influenced rail development in Wisconsin. The first

factor is the state’s geographical position between the Great Lakes and the

Northwest. The second factor is the timber resources in the northern half of

the state. The partial depletion of the forest lead to many miles of abandon

railroad in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s. However, the substantial

agricultural and industrial traffic, plus the link to the northwest, kept

railroads an important form of freight transportation in the state.

Wisconsin railroad mileage peaked

in 1920 at 7,327 miles. But from 1920 to 1929, abandonments exceeded new

construction and this pattern continued, and accelerated, for many decades. The

1970’s proved especially difficult for the freight rail industry. Intermodal

competition, economic regulation, the energy crisis, and a recession all

contributed to the distress of the railroad industry. In the early 1980s,

deregulation of the rail industry improved rail’s position to offer competitive

rates for freight service. The number of abandon miles finally slowed

reflecting a growing stability in freight rail. In Wisconsin, larger railroads

abandon or sold large percentages of their lines to newly formed regional railroads.

Also, the state acquired nearly 600 miles of abandon lines for operation by

short line carriers.

Today Wisconsin has 12 railroads

operating on nearly 4,500 miles of track. The state has three class I

Railroads, five regional Railroads, two local Railroads, and two switching

& terminal Railroads. These railroads combine to carry nearly 94,000,000

tons of freight in 1988, more than 1,046,000 carloads. The leading commodity

originating within the state was nonmetallic minerals (over 3,833,000 tons).

The leading commodity to terminate by rail in Wisconsin was coal (nearly

42,000,000 tons).

Passenger Rail

The first rail passenger service in

Wisconsin began in 1851, carrying passengers from Milwaukee to Waukesha. The

wood burning locomotive of the Milwaukee & Mississippi Railroad Company

traveled at speeds of up to thirty mile an hour during the short trek. By 1867,

passenger rail connected Milwaukee with Chicago, as well as the Twin Cities.

From this time until the end of World War I (1918), rail passenger service

continued to prosper and became the predominant mode of travel.

Following World War I, the

automobile became a major competitor of the train. Railroads continued

improving the quality of passenger service into the 1940s, but the number of

miles was declining. Beginning in the 1950s, railroads de-emphasized passenger

trains and rapidly abandon services, to the point that in the late 1960s,

people feared train service would be reduced to just a few routes in the

Northeast.

In 1970, concern over the possible

extinction of passenger trains in many areas of the country prompted Congress

to create Amtrak to operate a national system. Since this time, Amtrak has

experienced a number of staff reorganizations and route changes. Two Amtrak

routes currently run in Wisconsin. The Hiawatha service runs between Milwaukee

and Chicago six times daily. The Empire Builder runs once a day between Chicago

and the Twin Cities, and out to the West Cost. Wisconsin Amtrak rail stations

are found in Sturtevant, Milwaukee, Columbus, Portage, Wisconsin Dells, Tomah

and La Crosse. Amtrak recently announced plans to extend passenger and express

cargo rail service to Fond du Lac and Janesville as part of a comprehensive

effort to preserve and expand existing rail networks.

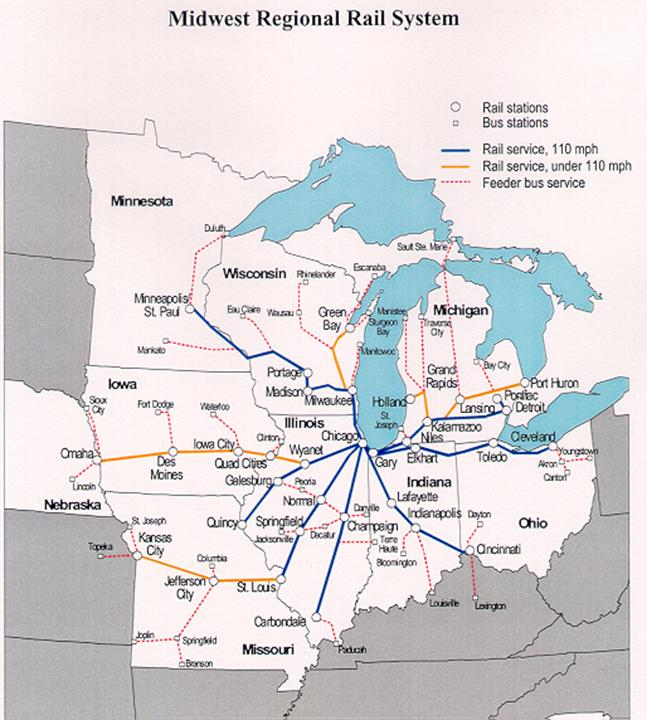

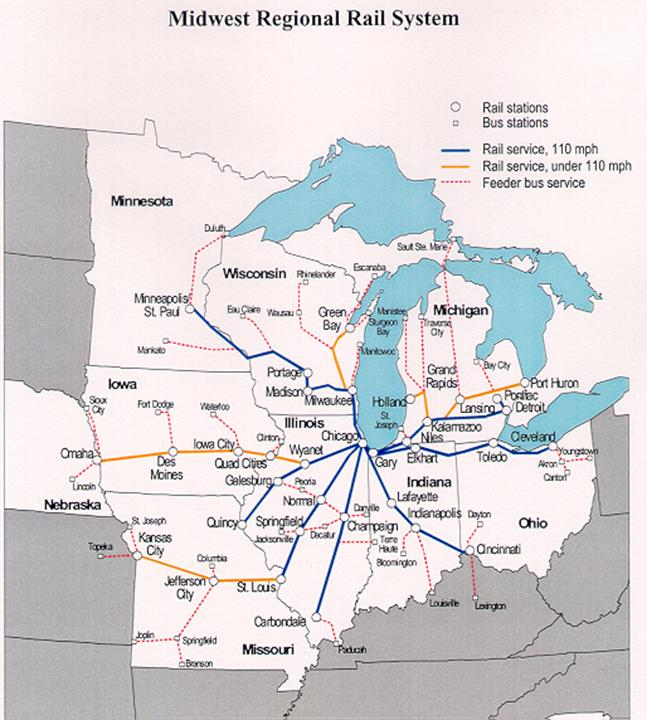

Midwest Regional Rail System

The major plan elements of the

Midwest Regional Rail System (MWRRS) include:

·

Use of 3,000 miles of existing rail

rights-of-way to connect rural, small urban, and major metropolitan areas.

·

Operation of a “hub-and-spoke” passenger rail

system providing through-service in Chicago to locations throughout the

Midwest.

·

Introduction of modern train equipment operating

at speeds up to 110 mph.

·

Provisions of multi-modal connections to improve

system access.

·

Improvement in reliability and on-time

performance.

Within the context of the larger

MWRRI, Wisconsin is involved with the Tri-State II High Speed Rail Study. This

study is nearing completion and evaluates various high-speed options in the

Chicago-Milwaukee-Twin Cities corridor. The analysis has built on the results

of two previous corridor studies: the Tri-State High Speed Rail Study, and the

Chicago-Milwaukee Rail Corridor Study. The Tri-State II Study has looked beyond

the MWRRI and will provide policy makers with information needed to evaluate

and choose among route and technology alternatives in the tri-state area.

As part of the MWRRI, WisDOT began

analysis on the high speed rail corridor between Milwaukee and Madison in

November of 1999. This corridor is part of the first phase of the initiative

and proposed train speeds are up to 110 mph. WisDOT is conducting planning,

engineering and environmental studies along the existing 85 mile long rail

corridor. Service could begin as early as 2003, with six trains daily in each

direction (three of them are proposed to be express service with no stops).

Service (110 mph) between Madison and the Twin Cities could begin in 2005,

while service (79 mph) between Milwaukee and Green Bay is scheduled to begin in

2007. The Milwaukee-Chicago corridor is scheduled for upgrade to 110 mph in

2009, with 10 trains daily in each direction.

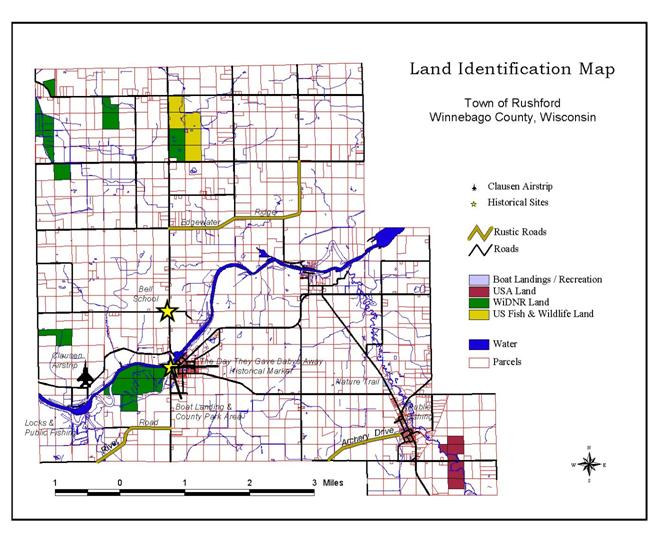

AIRPORT SERVICE

Wittman Regional Airport in Oshkosh

is the primary air service for the region.

Wittman Regional offers daily commuter flights to Chicago's O'Hare International

Airport including charter and daily freight service.

Aviation activity in Wisconsin is measured through the use

of information provided by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and

developed from the Wisconsin Department of Transportation (WisD0T) records and

files. Reporting sources include Air Traffic Control Facilities, Flight Service

Stations, Airport Managers and Scheduled Air Carriers.

This report concentrates on activity changes that took place during 2000 as

compared to 1999. The yearly totals for aviation activity at airports with

control towers were taken from the monthly data reports submitted by the FAA

control towers.

The following summarized data is used in developing and measuring Wisconsin

aviation trends.

LANDING FACILITIES

Currently, there are 720 aircraft landing areas known to exist in

Wisconsin. Table 1 summarizes these landing areas.

TABLE 1

Landing Facilities on Record

|

|

1996

|

1997

|

1998

|

1999

|

2000

|

|

Airports open to the public

|

133

|

133

|

132

|

131

|

136

|

|

Publicly owned

|

95

|

95

|

97

|

97

|

98

|

|

Privately owned

|

38

|

38

|

35

|

34

|

38

|

|

Private use airports

|

408

|

395

|

403

|

419

|

426

|

|

Heliport

|

108

|

111

|

115

|

120

|

131

|

|

Seaplane bases

|

28

|

26

|

26

|

27

|

27

|

|

Military/Police fields & helipads

|

7

|

7

|

7

|

7

|

7

|

|

Total

|

684

|

673

|

683

|

704

|

727

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Location on the National Plan of

Integrated Airport Systems (NPIAS)

|

88

|

88

|

88

|

88

|

83

|

|

Location on the State Airport System

Plan

|

100

|

100

|

100

|

100

|

100

|

|

Airports with Instrument Approaches

|

75

|

81

|

81

|

83

|

80

|

TABLE 2

Tower Reported Operations by Airport

|

Location/Airport

|

Tower

Hours

|

1996

|

1997

|

1998

|

1999

|

2000

|

% Change

(99-00)

|

|

Milwaukee-Mitchell

|

24 hours

|

200,963

|

212,609

|

219,087

|

221,866

|

221,855

|

0

|

|

Madison-Dane County

|

6 a.-11 p.

|

154,860

|

145,504

|

144,712

|

153,200

|

134,692

|

-13.7

|

|

Oshkosh - Wittman

|

6 a.-10 p.

|

84,027

|

83,260

|

88,809

|

115,500

|

104,393

|

-10.6

|

|

Waukesha - Crites Field

|

6 a. - 9 p

|

68,464

|

87,090

|

89,662

|

96,160

|

90,472

|

-6.3

|

|

Kenosha - Kenosha Regional

|

7 a.-9 p.

|

67,088

|

85,667

|

78,826

|

87,545

|

89,221

|

1.9

|

Statewide total operations for 2000 decreased by 4.87% or

51,487 operations. Only three out of eleven tower airports reported increases

in 2000. Kenosha Regional, Appleton-Outagamie, and Central Wisconsin are the

only airports that reported increases Air carrier operations decreased by 7.93%

and air taxi operations increased by 7.86% statewide. General aviation

operations increased by 6.12% for itinerant traffic and decreased by 7.96% for

local operations.

In all there are basically three types of airports. 1) Large

Municipal/Private airports that are state and federally funded such as Mitchell

County airport in Milwaukee. 2) Small private airports that are for the owner’s

use only, and 3) Small private airports that are used by the owner and only

invited others. In the Town of Rushford one such private airport exists,

Clausen Airstrip.

All airports must be state approved through the issuance of

a certificate for site use in Wisconsin. This process involves the owner

applying to the State DOT. Once an

application is received the state notifies the county and community that an

application has been received and requests comment on opinion and if there are

any local regulations are at issue. It is important to note that the state

certificate does not pre-empt local regulations. As airports are approved the

state forwards information on their location to the Federal Aviation

Administration where they are officially noted on aviation maps.

If a local unit of government wishes, they may regulate

local private airports by ordinance. Typical regulations include:

1. Appropriate

use within the zoning district.

2. Size,

location and number of housing/storage facilities.

3. Hours

of operation.

4. Noise

and pollution.

It is typical of most airports that they start out small and

in rural locations. As time passes and development occurs around these facilities,

inevitably conflict arises. Local governments can act proactively to avoid

these conflicts by planning for growth around existing facilities. In addition,

a regulatory approach can be considered if there is appropriate need.

SNOWMOBILE TRAILS & OPERATIONS

1999 - 2000 Snowmobile Program Report Summary

Wisconsin Law requires that a conservation warden or

law enforcement officer be notified of any snowmobile accident that results in

an injury requiring medical treatment by a physician. In addition, the operator(s)

involved in these "reportable accidents" must file a written report

with the Department of Natural Resources within 10 days of the accident,

insofar as they are capable of doing so.

All fatal snowmobile accidents are investigated by

Conservation Wardens. The 1999-2000 Snowmobile Program Report summary is

compiled from those investigations. There were 38 fatal accidents reported for

the fiscal year 1999-2000 (fiscal year runs from July 1-June 30).

CAUSES

OF THE FATAL ACCIDENTS

The leading cause of death was colliding with an object (tree, bank, car, etc).

The leading contributing factors were, excessive speed and alcohol consumption.

In several cases, speed estimations according to witnesses were reported to be

as high as 100 mph. There were 13 fatal crashes that Conservation Wardens could

directly identify excessive speed as a contributin factor to the death of the

operator/passenger. Of those 13 fatals, 10 of those who died consumed alcohol.

Alcohol was identified as another contributing factor. The law expressly states

a person is under the influence of alcohol once their blood alcohol level

reaches 0.10. Sixty-six percent or 25 of the victims who had known toxicology

reports performed, showed they had consumed some alcohol. There were 8 victims

that were not able to be determined and only 5 victims had no alcohol in their

system at the time of death. Of the total number of victims who had consumed

alcohol, 80% had a blood alcohol reading of 0.10 or higher. With the blood

alcohol readings, 8 were determined to be 0.20 and above.

WHO

WAS INVOLVED

All but 2 of the fatal accident victims were males. The ages of all fatalities

ranged 17-68 years, with the average age 34. Of the 38 fatal accidents, 35 of

the victims were Wisconsin residents while 3 were from surrounding states,

Illinois and Minnesota. The largest percentage of those people killed were age

21-29 (39%). The second largest age group was 30-39 (27%). No one 16 years old

or younger were killed this reporting period. The majority of the victims had

not received formal Snowmobile Safety Training. Of the 38 victims, 30 were

known to have been wearing a helmet, 4 were not and 4 were not known.

WHEN

DO THESE ACCIDENTS OCCUR

A correlation was observed by reviewing fatality statistics for the past five

years. Inferences can be drawn as to the time of day these accidents occur and

day of the week. Not surprising, the majority of the people killed while

snowmobiling, were fatally injured on Friday, Saturday or Sunday. The times

that people were most likely to be involved in a deadly accident is between the

hours of 8:00pm - 3:00am.

|

Sheriff Snowmobile Patrol Citations:

|

Conservation Warden

Snowmobile Citations:

|

|

356

|

TOTAL CITATIONS

|

921

|

TOTAL CITATIONS

|

|

29

|

Operate Snowmobile w/o

Valid Registration (S-1)

|

147

|

Operate Snowmobile w/o

Valid Registration (S-1)

|

|

19

|

Failure or Improper Display

of Registration Number or Decal (S-2)

|

40

|

Failure or Improper Display

of Registration Number or Decal (S-2)

|

|

24

|

Operate Snowmobile w/o Possession

of Valid Certificate (S-3)

|

62

|

Operate Snowmobile w/o

Possession of Valid Certificate (S-3)

|

|

7

|

Failure to Transfer

Registration of Snowmobile (S-4)

|

8

|

Failure to Transfer

Registration of Snowmobile (S-4)

|

|

9

|

Give Permission to Operate

a Snowmobile not Registered (S-5)

|

38

|

Give Permission to Operate

a Snowmobile not Registered (S-5)

|

|

1

|

Transport Uncased Strung

Bow on a Snowmobile

(S-09)

|

0

|

Transport Uncased Strung

Bow on a Snowmobile

(S-09)

|

|

0

|

Shoot From a Snowmobile

(S-10)

|

1

|

Shoot From a Snowmobile (S-10)

|

|

1

|

Operate in Prohibited Area

on Lands Controlled By DNR (S-11)

|

19

|

Operate in Prohibited Area

on Lands Controlled By DNR (S-11)

|

|

78

|

Highway and Roadway

Violations (S-12)

|

112

|

Highway and Roadway

Violations (S-12)

|

|

0

|

Equipment Violation (S-14)

|

6

|

Equipment Violation (S-14)

|

|

8

|

Permitting Operation by

Person Incapable Because of Age, Physical or Mental Disability (S-15)

|

19

|

Permitting Operation by

Person Incapable Because of Age, Physical or Mental Disability (S-15)

|

|

3

|

Failure to Report

Snowmobile Accident (S-16)

|

2

|

Failure to Report

Snowmobile Accident (S-16)

|

|

22

|

Unreasonable Improper or

Careless Operation (S-17)

|

55

|

Unreasonable Improper or

Careless Operation (S-17)

|

|

1

|

Fail to Display Lights when

Required (S-18)

|

0

|

Fail to Display Lights when

Required (S-18)

|

|

25

|

Trespass 'Sec. 350.10(6)

through (13) Wis. Stats.'

(S-19)

|

35

|

Trespass 'Sec. 350.10(6)

through (13) Wis. Stats.'

(S-19)

|

|

1

|

Miscellaneous (S-20)

|

2

|

Miscellaneous (S-20)

|

|

0

|

Dealers Failing to Collect

Fee & Submit Registration Applications (S-12)

|

0

|

Dealers Failing to Collect

Fee & Submit Registration Applications (S-12)

|

|

0

|

Failure to Stop for Law

Enforcement Officer (S-22)

|

1

|

Failure to Stop for Law

Enforcement Officer (S-22)

|

|

1

|

Failure to Render Aid

(S-23)

|

1

|

Failure to Render Aid

(S-23)

|

|

18

|

Operate Snowmobile while

Intoxicated (S-24)

|

25

|

Operate Snowmobile while

Intoxicated (S-24)

|

|

14

|

Operate Snowmobile with

Alcohol Concentration Above .1% (S-25)

|

17

|

Operate Snowmobile with

Alcohol Concentration Above .1% (S-25)

|

|

4

|

Refuse to Take Intoxicated

Snowmobile Test (S-26)

|

3

|

Refuse to Take Intoxicated

Snowmobile Test (S-26)

|

|

1

|

Absolute Sobriety for

Persons Under 19 (S-27)

|

1

|

Absolute Sobriety for

Persons Under 19 (S-27)

|

|

6

|

Operate Snowmobile that

Makes Excessive or Unusual Noise (S-28)

|

153

|

Operate Snowmobile that

Makes Excessive or Unusual Noise (S-28)

|

|

1

|

Operate Snowmobile w/o

Muffler on Engine (S-29)

|

2

|

Operate Snowmobile w/o

Muffler on Engine (S-29)

|

|

1

|

Cause Injury By Intoxicated

Operation of Snowmobile (S-30)

|

0

|

Cause Injury By Intoxicated

Operation of Snowmobile (S-30)

|

|

13

|

Operate w/o Trail Use

Sticker (S-33)

|

127

|

Operate w/o Trail Use

Sticker (S-33)

|

|

0

|

Operate (Manufacture or

Seller) Snowmobile w/o Functioning Muffler (S-34)

|

9

|

Operate (Manufacture or

Seller) Snowmobile w/o Functioning Muffler (S-34)

|

|

69

|

Failure to Comply with

Regulatory Signs (S-35)

|

36

|

Failure to Comply with

Regulatory Signs (S-35)

|

TRAILS

Within the State of Wisconsin there are approximately 22,000

miles of trails. In Winnebago County there are approximately 98 miles of

trails. These trails are categorized as either state funded trails or club

trails. In the Town of Rushford the Eureka Belt Busters maintain two segments of

trail, which pass through the township. While not typically thought of as part

of the transportation system, snowmobile trails provide a seasonal

transportation network that can greatly impact a community.

Wisconsin snowmobilers are proud of the statewide trail

system that ranks among the best in the nation. This trail system would not be

possible without the generosity of the thousands of land owners around the

state as 70% of all trails are on private land. Trails are established through

annual agreements and/or easements granted by these private property owners to

the various snowmobile clubs and county alliances throughout the state.

Snowmobile club members work closely with landowners in the

placement of the trails. They also assist by performing pre-season preparation,

brushing, grading, singing the trails, trail grooming, safety inspections of

the trails and fund raising to support the trail projects. This cooperation

results in the promotion of safe, responsible snowmobiling, and that benefits

everyone. Under Wisconsin State law, Sections 350.19 and 895.52, landowners are

not liable for injury on their property when they have granted permission for

snowmobiling.

Registration fees and the gas tax on 50

gallons per registered snowmobile help fund nearly 16,000 miles of snowmobile

trails. Specifically, registration fees fund a combination of trail aids, law

enforcement, safety education, registration systems and administration. Gas tax

revenues are dedicated solely to the trails program.

Registration fees and the gas tax on 50

gallons per registered snowmobile help fund nearly 16,000 miles of snowmobile

trails. Specifically, registration fees fund a combination of trail aids, law

enforcement, safety education, registration systems and administration. Gas tax

revenues are dedicated solely to the trails program.

MISCELLANEOUS PROVISIONS FOR SNOWMOBILE

OPERATION

No person shall operate a snowmobile in the following

manner:

·

At a rate of speed that is unreasonable or

improper under the circumstances.

·

No snowmobile may be operated at a speed of

greater than 50 miles per hour during the hours of darkness (1/2 hour after

sunset to ½ hour before sunrise) This restriction applies to all lands. NOTE:

there may be more restrictive speed limits posted by municipalities and within

counties as needed to ensure the safety of riders.

·

Snowmobiles not registered in the State of

Wisconsin must display a Trail Pass to use Wisconsin trails.

·

On the frozen surface of public waters within

100 feet of a person not in or upon a vehicle or within 100 feet of a fishing

shanty unless operated at a speed of 10 miles per hour or less.

·

Between the hours of 10:30 p.m. and 7:00 a.m.

when within 150 feet of a dwelling at a rate of speed exceeding 10 miles per

hour.

·

In any careless way so as to endanger the person

or property of another.

·

On private property of another without the

consent of the owner or lessee. Failure to post private property does not imply

consent for snowmobile use.

·

In any forest nursery, planting area or on

public lands posted or reasonably identified as an area of forest or plant

reproduction when growing stock may be damaged.

·

On a slide, ski or skating area except for the

purpose of serving the area, crossing at places where marked or after stopping

and yielding the right-of-way.

·

On or across a cemetery, burial ground, school

or church property without consent of the owner.

·

On the lands of an operating airport or landing

facility except for personnel in performance of their duties or with consent.

·

On Indian lands without the consent of the

tribal governing body or Indian land owner.

·

On lands owned or under the control of the DNR

and on federal waterfowl production areas, except where their use is authorized

by posted notice or permit.

·

At a speed not to exceed 10 miles per hour and

yield the right-of-way when traveling within 100 feet of a person who is not in

or on a snowmobile.

UNIFORM TRAIL DESIGN STANDARDS

The Department of Natural Resources, in cooperation with the

Department of Transportation, after public hearing, shall promulgate rules to

establish uniform trail and route signs and standards relating to operation

thereon as authorized by law. The authority in charge of the maintenance of the

highway shall place signs of a type approved by the Department of Natural

Resources and the Department of Transportation on highways under its

jurisdiction where authorized snowmobile trails cross.

LOCAL ORDINANCES

Counties, towns, cities and villages may regulate snowmobile

operation on snowmobile trails maintained by or on snowmobile routes designated

by the county, city, town or village.

LOCAL ORDINANCE TO BE FILED

Whenever a town, city or village adopts an ordinance

designating a highway as a snowmobile route, and whenever a county, town, city

or village adopts an ordinance regulating snowmobiles, its clerk shall

immediately send a copy of the ordinance to the Department and to the office of

law enforcement agency of the municipality and county having jurisdiction over

such street or highway.

BOATING & SURFACE WATER TRANSPORTATION

The WiDNR boating program in the Bureau of Law Enforcement

has a wide range of duties and responsibilities. The eight major areas of

responsibilities are:

·

Boating safety education

·

Boating enforcement

·

Boat lien/theft investigation

·

Municipal ordinance review and administration

·

Waterway marker permitting and administration

·

Boat accident investigation, reporting and

administration

·

Designated mooring area review and approval

·

Underwater archaeology protection

Boating Enforcement

State conservation wardens and municipal patrol officers

provide on-the-water enforcement of boating laws. In recent years much emphasis

has been placed on enforcement of boating while intoxicated laws and personal

watercraft enforcement. The United States Coast Guard also provides enforcement

in some areas of the state.

The boating program administers funding to municipal water

safety patrols to reimburse them for up to 75% of their operating expenses. In

1999, municipal patrols received $1,100,00. In order to promote statewide

uniformity and consistency among agencies conducting boating enforcement, the

boating program also conducts yearly training sessions on new laws, policies

and enforcement techniques for all municipal boat patrols.

Municipal Ordinance Review

This program, designed to address local boating concerns and

conditions, assists local municipalities in drafting local boating regulations

tailored to local conditions. Authority for local municipalities to enact local

regulations is found in s. 30.77(3), Wis. Stats. Ordinances are then required

by statute to be submitted to the Department for review. Ordinances are

reviewed for consistency with State and Federal law. Any suggested changes and

comments with regard to the legality of the regulations are provided to the

local municipality. If a municipality enacts an ordinance which the Department

has found to be inconsistent with statutory requirements, the Department may

challenge the ordinance in court.

Waterway Marker Permitting and Administration

This program provides a permitting process for uniform

marking of waters of the state through the placement of aids to navigation.

Conservation wardens inspect individual sites and recommend approval or

disapproval of applications for placement of waterway markers. The boating

program then reviews the application for compliance with state and federal

requirements and either approves or denies the permit. The boating program also

retains a permanent record of all approved buoy applications[iv].

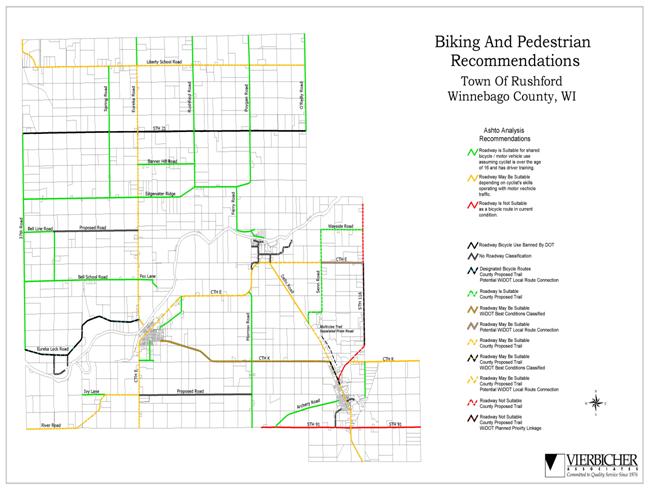

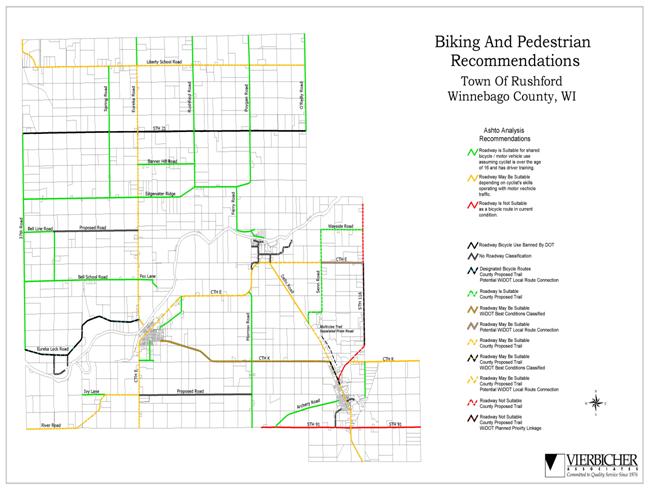

BIKEWAY & PEDSTRIAN MOBILITY ACCOMODATIONS

According to the 1991 “Guide

for the Development of Bicycle Facilities”, the national planning and

design standards published by the American Association of State Highway and

Transportation Officials (AASHTO), “Bicycle facility planning is commonly

thought of as the effort undertaken to develop a separated bikeway system

composed completely of bicycle paths and lanes all interconnected and spaced

closely enough to satisfy all the travel needs of bicyclists. In fact, such

systems can be unnecessarily expensive and do not provide for the vast majority

of bicycle travel. Existing highways, often with relatively inexpensive

improvements, must serve as the base system to provide for the travel needs of

bicyclists. Bicycle paths and lanes can augment this existing system in scenic

corridors or places where access is limited. Thus, bicycle transportation

planning is more then planning for bikeways and is an effort that should

consider many alternatives to provide for safe and efficient travel”.

Not all cyclists are alike – the needs of the experienced

adult rider differ greatly from less skilled, casual bicyclists and children.

The purpose of this section within the Town of Rushford’s Comprehensive Plan is

to identify desirable bicycle facility routes within the Town of Rushford

noting appropriate linkages between route and adjacent communities.

Various environmental factors combine to determine the

suitability of streets and roadways for bicycle travel. However, personal

factors also strongly influence the decision to bike or not to bike on any

given roadway. Cyclists of differing skills will rate the suitability of the

same street differently, based on their perception of safety along the route and

their desire to ride for recreation or transportation purposes. For this

reason, any methodology to rate roadway suitability must begin with an

understanding of the different types of bicyclists.